![]()

![]()

When Israeli footballer Eran Zahavi received a proposal to play in the Chinese league, he wasn’t very keen on moving there, despite the large sums of money he was offered. He deliberated for a long time, looked into other options, and even an astronomic salary was unable to make him rush into signing the contract.

Only when he traveled to the city of Guangzhou and received a promise from the Chabad emissary there, Rabbi Rosenberg, that they would make sure that he and his family had kosher food and would perform a proper Shabbat meal and Kiddush for the family every Friday evening, the footballer was persuaded to sign the multi-million-dollar contract.

The Chabad representation in China and the Zahavi example are the essence of the ties between the Far East country and Israel and the Jewish world—financial ties of businesspeople or representatives of Israeli companies, who travel there for a relocation or for short periods for business purposes. In fact, there is no real Jewish community in China today, and the needs of Jewish businesspeople are catered by Chabad houses located in strategic places near the work and business centers.

While the connection today is basically a business relationship, a review of history reveals that there were quite a few Jewish communities that found their place in China throughout the years. In recent years, the Chinese government has actually been trying to shed light on China’s Jewish past, and it even sponsored a unique exhibition at Bar-Ilan University featuring the Jewish communities that used to live in China in the past.

There are 20 students from China studying at Bar-Ilan University, and some of them are even researching the Jewish-Chinese connection in different directions. One of them, Xiu Gao, has been there for four years and is studying the way the image of the Jew was reflected in Shakespearean texts that were translated into Chinese. She believes this will illuminate to the perception of Jews in the eyes of the Chinese during different periods. Another student, Amos Lin from Singapore, is researching Jewish history in Southeast Asia, including the image and influence of the Iraqi merchants on China and Singapore. According to Lin, these studies could influence Asia in the future, as they have historical value and contain proof of the establishment of strong ties and influence between the Jews and the Chinese.

Dr. Gurevitch, who translated the book “The Jews in Modern China,” says there are three distinguishable waves of Jewish immigration to China in modern times. The first was in 1840, when Jews of Sephardic descent arrived in China from the Middle East and from other areas in Asia. These Jews, who came from areas under British control, had a British citizenship; this allowed them to engage in trade, particularly in Hong Kong and Shanghai. The merchants, mainly from Baghdad, were highly successful and turned into a very active consortium in China. The Jewish merchants lost their hold in China in 1937, after the Japanese occupation.

The second wave of Jewish immigration arrived in China under considerably worse conditions. It included Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe who were forced to leave their homes following repeated riots. Jews from Russia crossed the border into China and resided primarily in the Harbin area. Later, they moved southward, settling in the big cities of Shanghai, Tianjin and Qingdao. These Jews became deeply rooted in local society and left their own mark on it; there is no doubt that their presence had a significant contribution to China’s economic and cultural development.

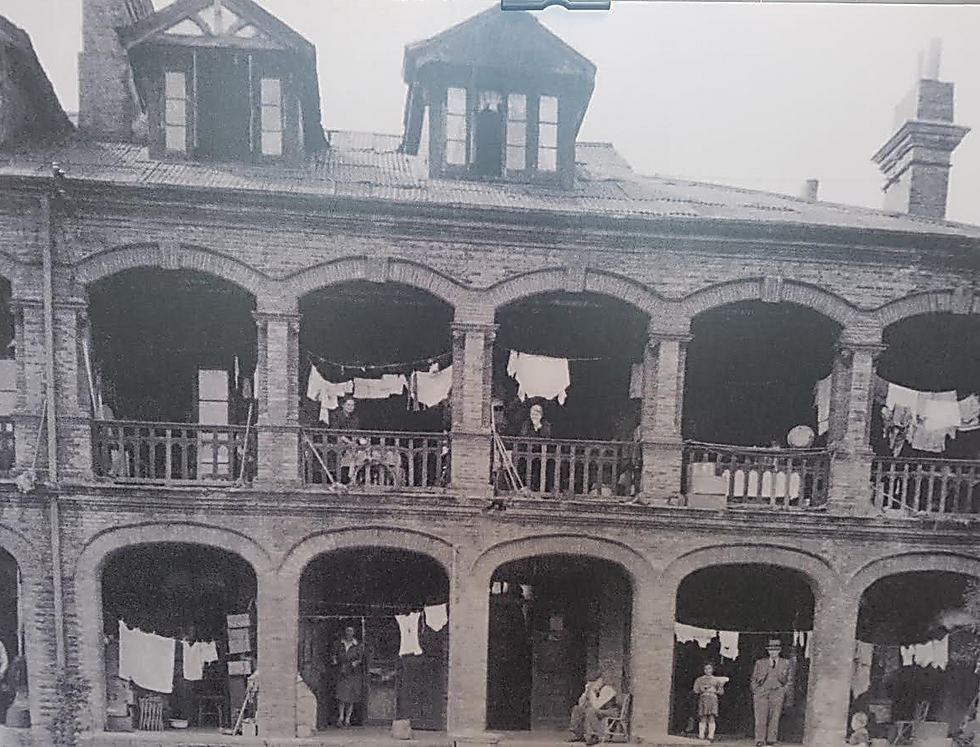

The Chinese talk about the third wave of Jewsish immigrants with a lot of satisfaction, as it helped save the lives of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. More than 30,000 Jews arrived in Shanghai from 1933 to 1941 after escaping from Europe. In fact, Shanghai alone took in more Jewish refugees than Canada, Australia, India, South Africa and New Zealand combined.

Although China was under the occupation of Japan—an ally of Germany—Japan refused to carry out the “final solution” on Shanghai’s Jews, although a sort of ghetto was built in the city, to which all of the country’s Jews were sent. The Jews suffered from difficult conditions in the ghetto but eventually survived, and thanks to help from the US Jewry, they managed to get through the war. Following the war, the Jews left China, some immigrating to Israel and others heading to the United States.

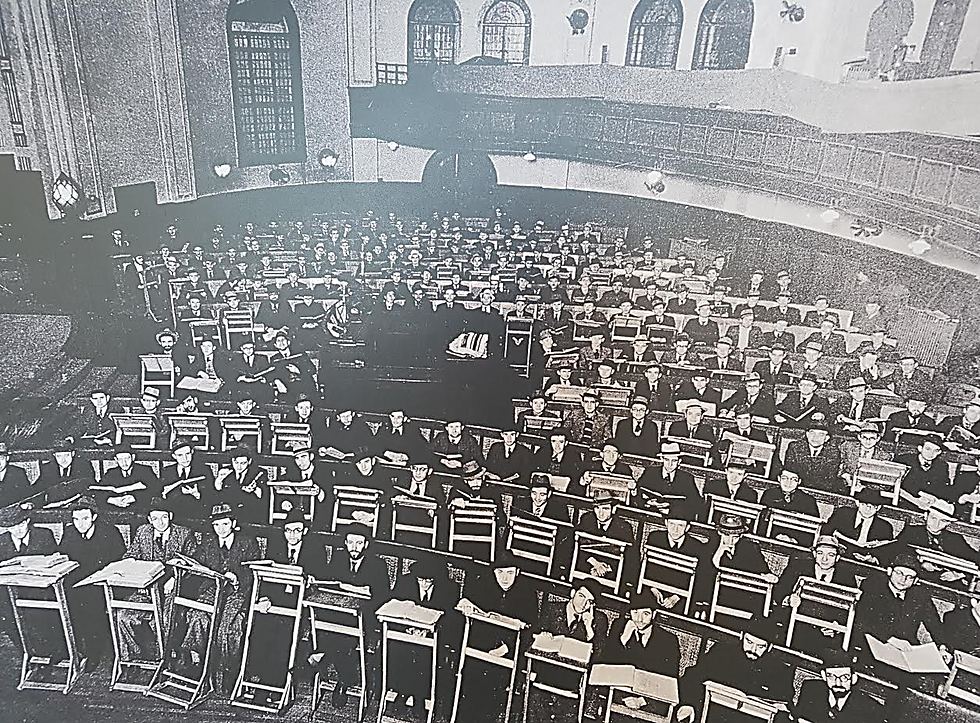

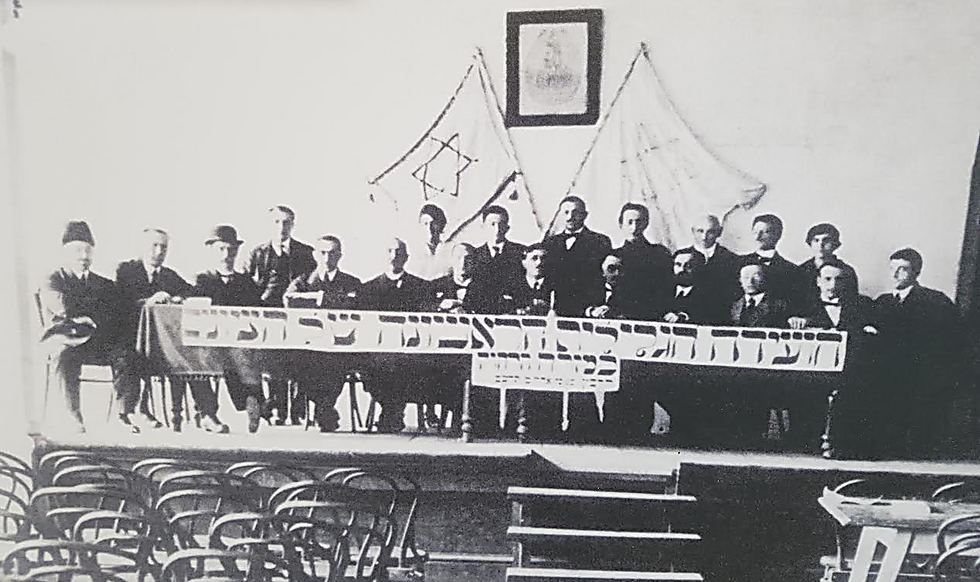

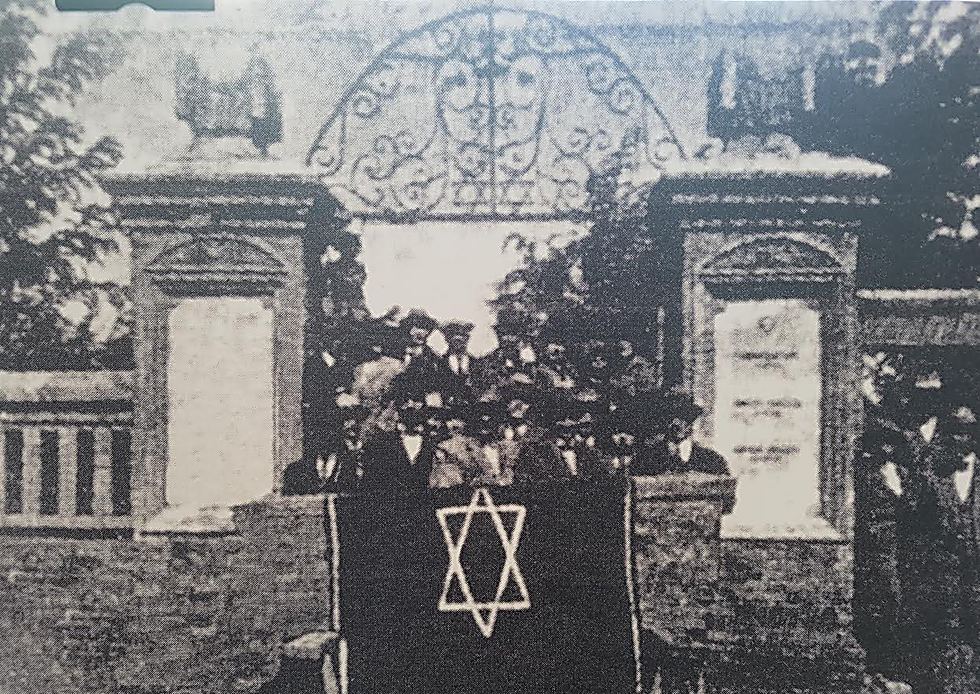

The story of China’s Jews includes their surprising involvement in local society and their success in establishing a vibrant Jewish community with social, religious and communal activity. They established many synagogues, hospitals, schools, newspapers and cultural institutions.

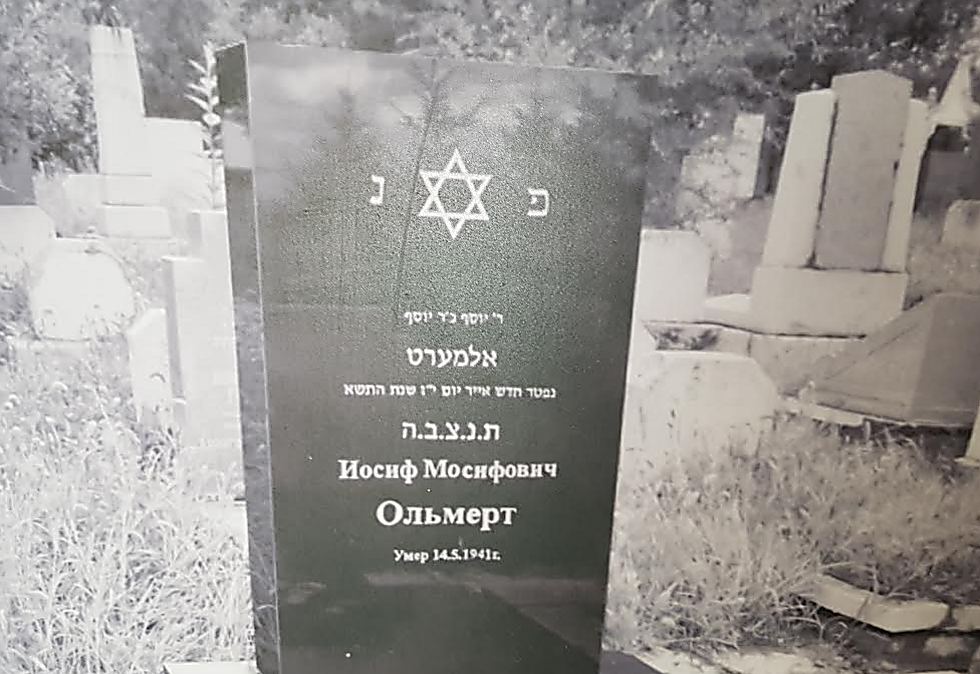

According to Dr. Gurevitch, it was an exceptional success, particularly in light of the fact that the Jews from the second wave, those who fled the riots in Russia, arrived in China with almost nothing and were forced to build the community from scratch. Their success did not escape the eyes of the world Jewry, and over the years they received visits and support from many figures like Albert Einstein, Joseph Trumpeldor, and Mordechai Olmert (the father of former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert), who was one of the founders of the Beitar organization in China in 1929.

The Jewish merchants imported to China some aspects of European culture, reflected in stores and cafés with a European flair. Chinese Jews also worked in workshops and were involved in cultural and media activities. Since the establishment of diplomatic ties with Israel in 1992, the Chinese regime has been motivated to tighten its relations in Israel, including documenting and cherishing the Chinese-Jewish relationship from the previous century. At the same time, the number of Israeli students studying in China is increasing, and there are also quite a few Chinese students in Israel.